U.S. Oil Going Places

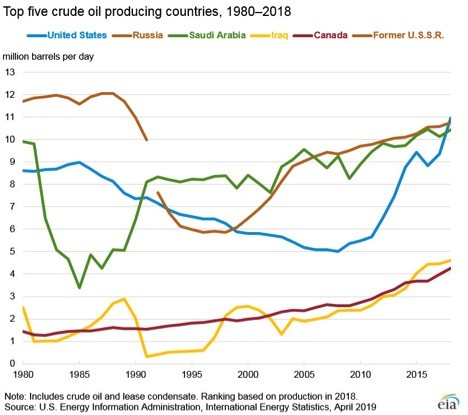

As we have noted in a prior edition of The Five Star Standard, the U.S. is set to become a net energy exporter.The U.S. has rapidly moved up to be one of the biggest (at times the biggest) oil producers:

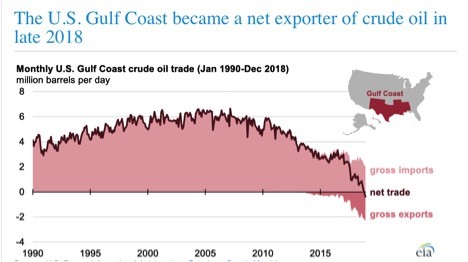

Indeed, In the last two months of 2018, the U.S. Gulf Coast already exported more crude oil than it imported. Monthly net trade of crude oil in the Gulf Coast region (the difference between gross exports and gross imports) fell from a high in early 2007 of 6.6 million barrels per day (b/d) of net imports to 0.4 million b/d of net exports in December 2018. As gross exports of crude oil from the Gulf Coast hit a record 2.3 million b/d, gross imports of crude oil to the Gulf Coast in December—at slightly less than 2.0 million b/d—were the lowest level since March 1986.

In 2018, U.S. net imports (imports minus exports) of petroleum from foreign countries averaged about 2.34 million barrels per day, equal to about 11% of U.S. petroleum consumption.1 This was the lowest percentage since 1957.

Petroleum includes crude oil and petroleum products. Petroleum products also include gasoline, diesel fuel, heating oil, jet fuel, chemical feedstocks, asphalt, biofuels (ethanol and biodiesel), and other products.In 2018, the United States consumed an average of about 20.5 million barrels of petroleum per day , or a total of about 7.5 billion barrels of petroleum products.

Where Does the Crude Go?

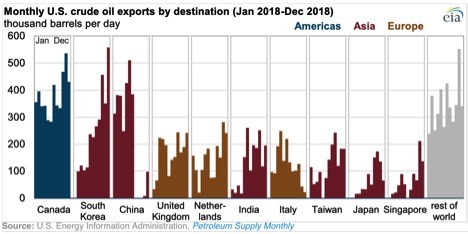

In 2018, U.S. exports of crude oil rose to 2.0 million barrels per day (b/d), nearly double the 1.2 million b/d rate in 2017. Export volumes by destination changed significantly during the year, as U.S. crude oil exports to China fell and exports to other destinations such as South Korea, Taiwan, and Canada increased.

In early 2018, the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP) in the Gulf of Mexico was modified to enable the loading of vessels for crude oil exports. LOOP is currently the only U.S. facility capable of accommodating fully loaded Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCC), vessels capable of carrying approximately 2 million barrels of crude oil.

After LOOP was modified to also allow exports, the increase in cargo scale led U.S. crude oil exports to surpass 2 million b/d for 25 weeks in 2018 compared with just 1 week in 2017. In addition to LOOP, other U.S Gulf Coast export facilities in and around Houston and Corpus Christi, Texas, have been investing in increasing the scale of U.S. crude oil export cargos.

In 2018, Asia was the largest regional destination for U.S. crude oil exports, followed by Europe, while, as in previous years, Canada was the largest single destination for U.S. crude oil exports. Canada received 378,000 b/d of U.S. crude oil exports, representing 19% of total U.S. crude oil exports in 2018. South Korea surpassed China to become the second-largest destination for U.S. crude oil exports in 2018, receiving 236,000 b/d compared with China's 228,000 b/d.

However, the distribution of U.S. crude oil exports by destination varied significantly from the first half of 2018 to the second half. In the first half of 2018, the United States exported 376,000 b/d of crude oil to China, which made China the largest single destination for U.S. crude oil exports for that period. However, in August, September, and October of 2018, the United States exported no crude oil to China. U.S. crude oil exports to China resumed in the final two months of the year but at much lower volumes. On average, the United States exported 83,000 b/d of crude oil to China in the second half of 2018.

Why Do We Export Crude?

It comes down to the quality of the oil that is being produced, versus the kind of oil U.S. refineries are built to process.

Over the years, U.S. crude oil has gotten progressively heavier and sourer (meaning it contains larger hydrocarbon molecules as well as more sulfur.) Globally, heavy crude production increased in places like Canada, Venezuela and Nigeria. A wide price differential developed between heavy, sour crudes and light sweet crudes like WTI and Brent. Because crudes that are heavy and/or sour can produce about the same amount of finished products as lighter, sweeter crudes, refiners had a strong financial incentive to process the discounted crudes.

So U.S. refiners spent billions of dollars installing fluid catalytic crackers (FCCs), cokers, and hydrotreaters that are needed to process heavy sour crudes. After investing all of that money into processing the heavy crudes, the economics of running Bakken or Eagle Ford crudes in a heavy oil refinery are far less appealing than running a heavy Canadian or Venezuelan crude.

Heavy oil refiners would rather simply continue to import oil more suited to their needs, while the light, sweet crudes coming out of the U.S. shale plays are often a better fit for certain foreign refineries. Or, logistically it may simply be easier for Canada, for instance, to import U.S. crude for their East Coast refineries, while they export their heavy oil from Alberta to U.S. refineries that are equipped to process it.

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://fsmetals.com/